Server-Side Rendering (SSR)

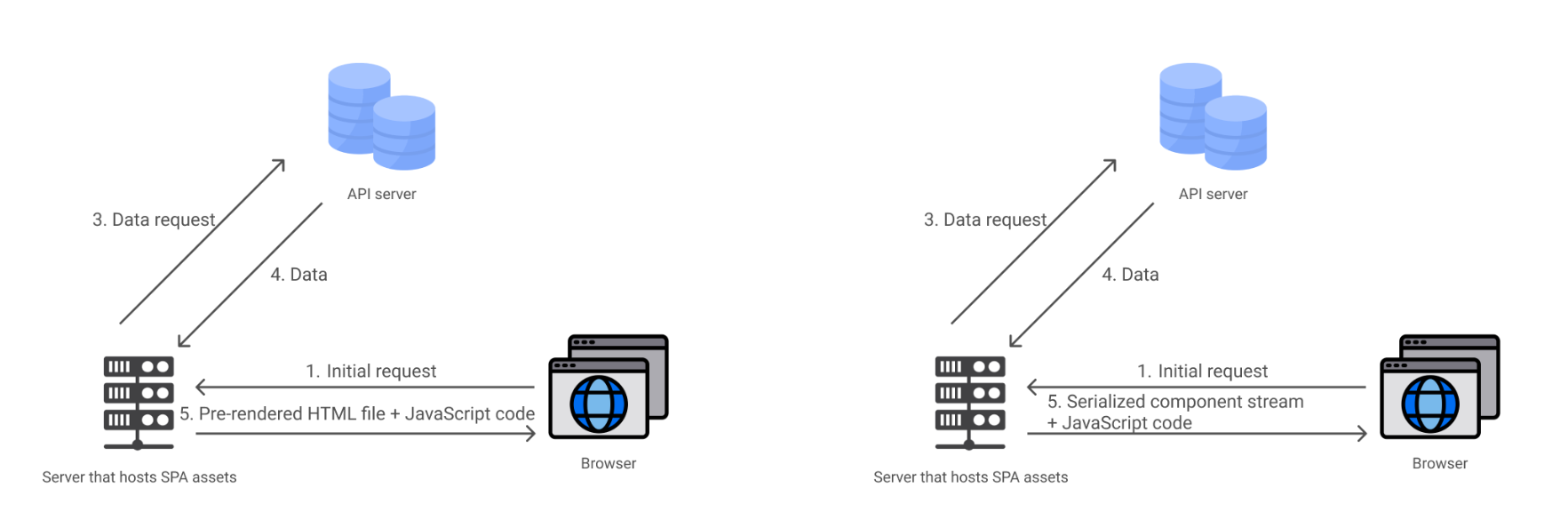

SSR reduces these issues by rendering the initial page in the server itself. After rendering the initial page, it

sends the pre-rendered HTML file to the browser along with the JavaScript code. If we take our example, when the user

requests the app, the server will first fetch the task list from the backend. Then, it will render the tasks page and

send the HTML file to the browser. Along with this, the server will also send the JavaScript code for the entire

application.

So, unlike in SPAs, when we use SSR, the browser will be able to immediately show the tasks page. This reduces the time

taken for FCP (first contentful paint) and consequently, vastly improves the user experience. Moreover, since it is the

server that fetches the

task list, the user’s internet speed is going to be immaterial. And the server can fetch the data a lot faster because

the request goes through a private network.

The drawbacks of SSR

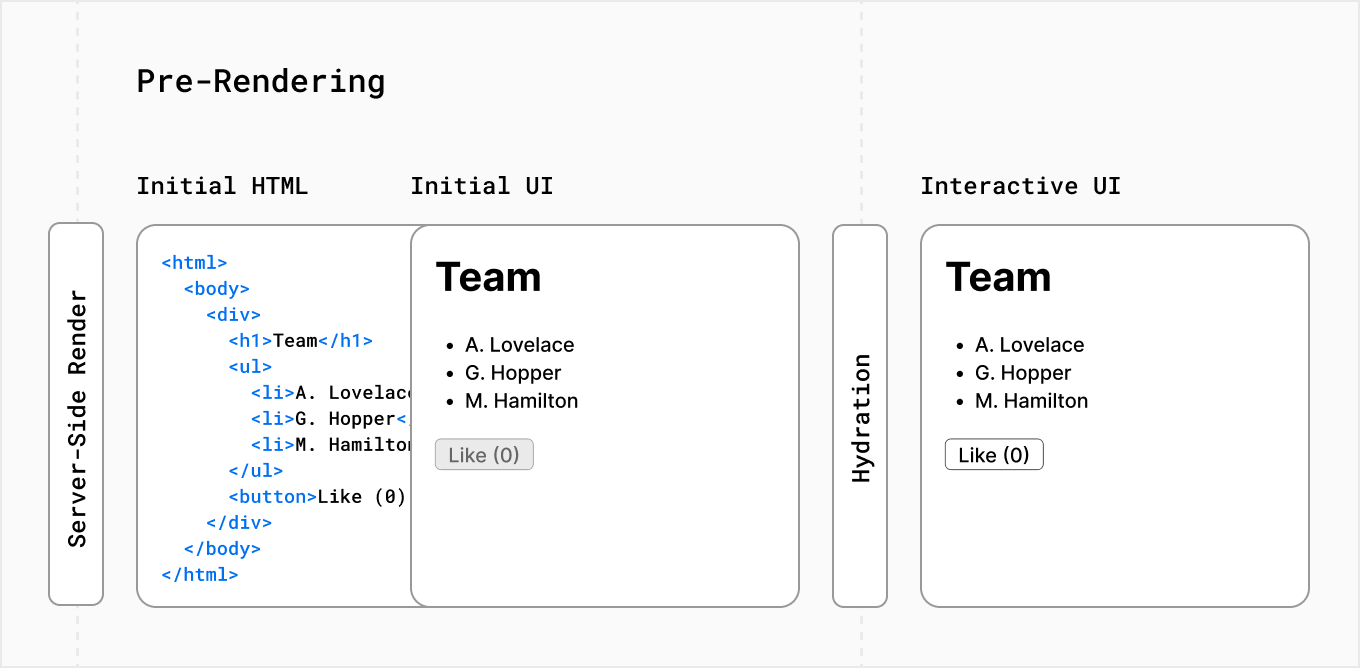

However, the page will not become interactive immediately and the browser needs to wait till it completes downloading

the JavaScript bundle to add interactivity. Once it completes downloading, then the HTML page can be hydrated using the

JavaScript code. So, the user will have to wait for a while before they can start interacting with the app. For

instance, if the user wants to add a task by clicking on the “Add Task” button, they will have to wait till the browser

hydrates the HTML file. This is going to result in a poor Time to Interactive (TTI) score.

Additionally, once the browser loads the initial page, then this app is going to behave like a SPA. So, if the user

navigates to the reminders page, then the browser is going to render this page and send a request to fetch the list of

reminders. On that account, the only real advantage of SSR comes at the initial page-load stage with the FCP score,

while TTI is going to be almost the same.